For over two centuries, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have endured the profound injustices of colonisation, dispossession, and systemic marginalisation.

From the very first European settlement to the ongoing struggles for recognition and justice, the impact of these historical wrongs is immeasurable. It is not only an affront to the sovereignty of our First Nations but a stain on the moral fabric of the nation itself.

Today, after years of battle for recognition, and a referendum that was soundly rejected, there is a palpable sense of betrayal. A promise to our ancestors, and to future generations, to secure justice through a treaty remains an unfinished chapter in the history of this country.

A Personal History of Struggle and Betrayal

I, like many others, carry with me the scars of this nation’s history. My family’s roots trace back to the lone survivor of the Waterloo Creek massacre, a brutal tragedy that epitomised the harshness faced by Indigenous peoples. My great grandfather, whose premeditated murders went unpunished by an all-white jury in 1953, left us with a legacy of unresolved grief.

The injustice of his acquittal, followed by a retrial that only reiterated the failure of our legal systems to protect Indigenous lives, has reverberated through generations.

This history is not just personal—it is shared by thousands of families who have borne the weight of Australia’s colonial past. It is a history steeped in trauma, but also in resilience and resistance. Yet, despite the passage of time, the scars remain unhealed.

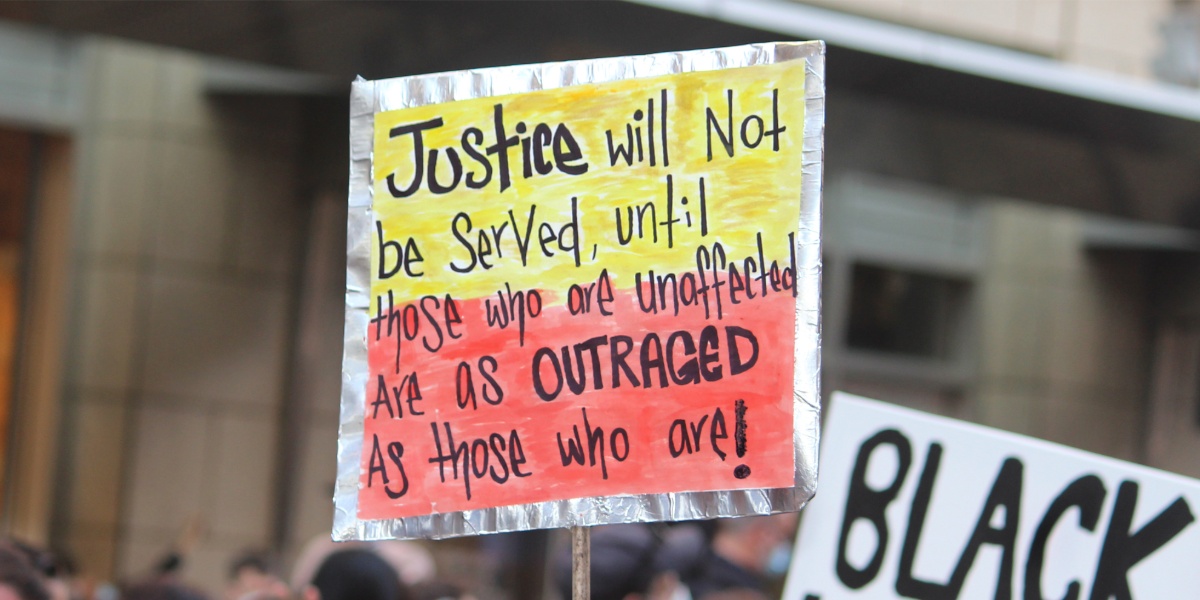

The pain of betrayal deepened after the failed referendum. We were offered the opportunity for meaningful recognition and change—a chance to shape a future that embraced the richness of our cultures, sovereignty, and humanity. But the result was a resounding defeat—a rejection of our rightful place in this nation.

The hurt from this betrayal cuts deep, as it feels like another conquest in a long line of attempts to diminish our identity and disregard our sovereignty.

The Urgency of a Treaty

A treaty is not merely a political document; it is a moral imperative. A treaty is an acknowledgment of the historical wrongs we have endured, and a declaration that the future will be different. It is the recognition of our sovereignty and the beginning of true reconciliation. This is not about a symbolic gesture or a political strategy. It is about rectifying centuries of injustice and ensuring that the next generation of First Nations peoples will inherit a nation that values and respects them, one that allows them to thrive in their own right, on their own land.

The failure of the referendum was a significant blow, but it is not the end of the road. It only reinforces the need for a comprehensive, multi-level treaty framework that goes beyond symbolic gestures to deliver real change. At the federal level, Australia must pass a Treaty Act that recognises the sovereignty, culture, and rights of First Nations peoples. This Act would create a national platform for negotiation and reparation, addressing land restitution and economic empowerment without infringing on private land ownership.

A Framework That Respects All Australians

The framework for a treaty must be multifaceted, addressing not only the needs of First Nations communities but also protecting the rights of non-Indigenous Australians. We must ensure that private land ownership is respected in the treaty process, ensuring that no private land is affected by these agreements. This is crucial for building trust across all communities and ensuring that a treaty is seen as a pathway to unity, not division.

A State Treaty Framework will tailor national principles to local contexts, ensuring that states and territories work with their First Nations peoples to address specific historical and contemporary issues. States must negotiate with local Indigenous communities to return Crown lands or provide resources and support for economic development initiatives focused on shared lands or areas designated for Indigenous use.

Moreover, Clan-Based Treaty Frameworks must recognise the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Each clan has its own history, its own language, and its own traditional laws. A treaty must allow for the self-determination of clans, ensuring that their traditional governance structures are respected and that land management systems are implemented with sovereignty at the core. It is crucial that these treaties are focused on Crown land, as well as unallocated government land, and that no private land is included in these agreements.

Empowering Communities from the Ground Up: The LGA Framework

At the grassroots level, Local Government Area (LGA) frameworks provide the opportunity for meaningful engagement with Indigenous communities. Local councils must empower Indigenous representatives to play a central role in community governance, ensuring that decisions are made with cultural sensitivity and respect for the land. Here, we focus on developing economic and social programs that close the gaps in education, employment, and housing, while ensuring that no private land is affected.

These local frameworks can facilitate Indigenous-led businesses, infrastructure projects, and job creation initiatives that promote self-sufficiency and economic growth, without encroaching on privately owned land. Public housing projects and community business hubs can be developed on public land, while partnerships with local schools and training institutions will empower young Indigenous people to thrive.

Credible Evidence: The Journals of Early Explorers and Settlers

It is vital to understand the context of the dispossession and trauma suffered by Indigenous Australians, which is evidenced in the journals and records of early European settlers and explorers. These documents reveal not just the extent of the violence and dispossession that took place, but the attitudes and justifications for such actions.

For example, the journal of John Oxley, an early explorer, reveals his observations of Indigenous peoples and their societies. Oxley acknowledged their complex social structures and made references to their stewardship of the land. However, his interactions with Aboriginal people were framed by the European belief in their ‘superiority’ and the idea that Indigenous cultures were inferior. The historical documents clearly show that early settlers sought to establish dominion over the land without recognition of the existing systems of land ownership and governance by Indigenous peoples.

Another early explorer, Major Thomas Mitchell, documented his encounters with Aboriginal groups in the 1830s. His journals are filled with references to the “savage” nature of Aboriginal peoples, which was a common colonial narrative used to justify violent practices like massacres and forced displacement. Mitchell, along with other explorers like William Wentworth and George Augustus Robinson, consistently viewed the Indigenous population as a barrier to settlement, leading to the widespread dispossession of their land.

The writings of Captain James Cook, whose arrival in 1770 marked the beginning of British colonisation, are also crucial to understanding the early interactions between Indigenous peoples and European settlers. Cook’s journal, while providing a detailed record of his encounters with Aboriginal people, depicts them through the lens of a colonial mindset that disregarded their sovereignty and established systems.

These early accounts, while invaluable in documenting the interactions between settlers and Indigenous peoples, also highlight the deeply ingrained racial prejudices and the belief that European civilisation was superior to Indigenous cultures. These journals reflect the justifications used to dispossess and subjugate Indigenous peoples, laying the groundwork for the systemic racism and inequality that continues to this day.

The Road Forward: Moving Beyond Betrayal

It is imperative that we do not let the pain of the referendum result become an obstacle to progress. While the outcome was disheartening, it does not diminish the need for a treaty—it amplifies it. The need for recognition, justice, and sovereignty is clearer now than ever before. The next steps in the treaty process must reflect the urgency of the situation. We need a comprehensive, legally sound treaty framework that spans Federal, State, Clan, and Local Government Areas, which protects private land ownership and focuses on restitution, empowerment, and justice for Indigenous communities.

We must keep pushing forward. We must honour the lives lost, the cultures suppressed, and the families torn apart by centuries of colonisation. This is our unfinished business, and we will not stop until justice is done. A treaty will not only restore dignity and sovereignty to First Nations peoples, but it will also build a stronger, more unified Australia—one that acknowledges the past, respects its Indigenous peoples, and moves forward in partnership. The time for a treaty is now, and it must be one that acknowledges our history, respects our land, and ensures a brighter future for all Australians.

We can only move forward together—so let us work to ensure the future we build is one where all Australians, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike, can stand in unity, with mutual respect and shared responsibility. This is the future we must build—a future forged by truth, respect, and the enduring spirit of First Nations peoples.

Jordan McGrady is a Gomeroi, Wirraway, Anaiwan, and Bigumbul man from Moree, NSW. A survivor of injustice and a leader in Treaty advocacy, he champions legislated sovereignty, truth-telling, and justice for First Nations through clan, state, and LGA-based frameworks.

Got something on your mind? Go on then, engage. Submit your opinion piece, letter to the editor, or Quick Word now.